Søren Kierkegaard

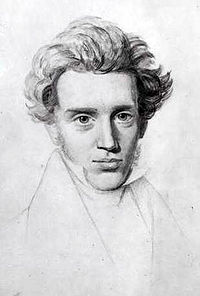

Sketch of Søren Kierkegaard by Niels Christian Kierkegaard, c. 1840 |

|

| Full name | Søren Aabye Kierkegaard |

|---|---|

| Born | 5 May 1813 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 11 November 1855 (aged 42) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Danish Golden Age Literary and Artistic Tradition, precursor to Continental philosophy,[1][2] Existentialism (agnostic, atheistic, Christian), Postmodernism, Post-structuralism, Existential psychology, Absurdism, Neo-orthodoxy, and many more |

| Main interests | Religion, metaphysics, epistemology, aesthetics, ethics, psychology, philosophy of religion |

| Notable ideas | Regarded as the father of Existentialism, angst, existential despair, Three spheres of human existence, knight of faith, infinite qualitative distinction, leap of faith |

| Signature | |

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (English pronunciation: /ˈsɔrən ˈkɪərkəɡɑrd/ or /ˈkɪərkəɡɔr/; Danish: [ˈsœːɐn ˈkʰiɐ̯kəˌɡ̊ɒˀ] (![]() listen)) (5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, writer and psychologist. He was born twelve years after the Battle of Copenhagen (1801), which started the decline of the Danish Kingdom. Kierkegaard wrote in reaction to speculative thinkers such as Niels Treschow (1751-1833) and Frederik Christian Sibbern (1785-1872).[4] He strongly criticised the philosophies of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and the Christianity of the State Church verses the Free Church. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives, focusing on the priority of concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment.[5] His theological work focuses on the difference between purely objective proofs of Christianity, which results in the Quest for the historical Jesus, and a subjective relationship to Christianity which comes from faith, and faith alone.[6] Many scholars consider him only in regard to Christian ethics and the institution of the Church.[7] His psychological works explore the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices.[8] His thinking was influenced by Socrates and the Socratic method. Kierkegaard's early work was written under various pseudonymous characters who present their own distinctive viewpoints and interact with each other in complex dialogue.[9] He assigns pseudonyms to explore particular viewpoints in-depth, which may take up several books in some instances, and Kierkegaard, or another pseudonym, critiques that position. He wrote many Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the "single individual" who might want to discover the meaning of his works. He said, "the task must be made difficult, for only the difficult inspires the noble-hearted".[10] Subsequently, scholars have interpreted Kierkegaard variously as, among others, an existentialist, neo-orthodoxist, postmodernist, humanist, and individualist. Crossing the boundaries of philosophy, theology, psychology, and literature, he is an immensely influential figure in contemporary thought.[11][12][13]

listen)) (5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, writer and psychologist. He was born twelve years after the Battle of Copenhagen (1801), which started the decline of the Danish Kingdom. Kierkegaard wrote in reaction to speculative thinkers such as Niels Treschow (1751-1833) and Frederik Christian Sibbern (1785-1872).[4] He strongly criticised the philosophies of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and the Christianity of the State Church verses the Free Church. Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives, focusing on the priority of concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment.[5] His theological work focuses on the difference between purely objective proofs of Christianity, which results in the Quest for the historical Jesus, and a subjective relationship to Christianity which comes from faith, and faith alone.[6] Many scholars consider him only in regard to Christian ethics and the institution of the Church.[7] His psychological works explore the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices.[8] His thinking was influenced by Socrates and the Socratic method. Kierkegaard's early work was written under various pseudonymous characters who present their own distinctive viewpoints and interact with each other in complex dialogue.[9] He assigns pseudonyms to explore particular viewpoints in-depth, which may take up several books in some instances, and Kierkegaard, or another pseudonym, critiques that position. He wrote many Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the "single individual" who might want to discover the meaning of his works. He said, "the task must be made difficult, for only the difficult inspires the noble-hearted".[10] Subsequently, scholars have interpreted Kierkegaard variously as, among others, an existentialist, neo-orthodoxist, postmodernist, humanist, and individualist. Crossing the boundaries of philosophy, theology, psychology, and literature, he is an immensely influential figure in contemporary thought.[11][12][13]

Contents |

Life

Early years (1813–1836)

Søren Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, had served as a maid in the household before marrying his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. She was an unassuming figure: quiet, plain, and not formally educated. She is not directly referred to in Kierkegaard's books, although she affected his later writings. His father was a "very stern man, to all appearances dry and prosaic, but under his "rustic cloak" manner he concealed an ardent imagination which not even his great age could blunt"[14] who read the philosophy of Christian Wolff. Soren preferred the comedies of Ludvig Holberg[15] and the writings of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing[16] and of course Socrates.

Based on a speculative interpretation of anecdotes in Søren's unpublished journals, especially a rough draft to a story called "The Great Earthquake",[17] some early Kierkegaard scholars argued that Michael believed he had earned God's wrath and that none of his children would outlive him. He is said to have believed that his personal sins, perhaps indiscretions like cursing the name of God in his youth or impregnating Ane out of wedlock, necessitated this punishment. Though five of his seven children died before he did, both Søren and his brother Peter Christian Kierkegaard, outlived him.[18] Peter, who was seven years Søren's elder, later became bishop in Aalborg.[18]

Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue, where he studied Latin and history, among other subjects. In 1830, he went on to study theology at the University of Copenhagen. But he wasn't interested in historical works, philosphy dissatisfied him, and he couldn't see "dedicating himself to Speculation".[19] He said, "What I really need to do is to get clear about "what am I to do", not what I must know". He wanted to "lead a completely human life and not merely one of knowledge."[20] Soren didn't want to be a philosopher[21] and he didn't want to preach a Christianity that was an illusion.[22] "But he had learned from his father that one can do what one wills, and his father's life had not discredited this theory."[23] He became a spy for God.[24]

Kierkegaard's mother died on 31 July 1834, age 66. One of the first physical descriptions of Kierkegaard comes from an attendee, Hans Brøchner, at his brother Peter's wedding party in 1836: "I found [his appearance] almost comical. He was then twenty-three years old; he had something quite irregular in his entire form and had a strange coiffure. His hair rose almost six inches above his forehead into a tousled crest that gave him a strange, bewildered look."[25]

Kierkegaard's father died on 8 August 1838, age 82. On 11 August, Kierkegaard wrote: My father died on Wednesday (the 8th) at 2:00 A.M.. I so deeply desired that he might have lived a few years more, and I regard his death as the last sacrifice of his love for me, because in dying he did not depart from me but he died for me, in order that something, if possible, might still come of me. Most precious of all that I have inherited from him is his memory, his transfigured image, transfigured not by his poetic imagination (for it does not need that), but transfigured by many little single episodes I am now learning about, and this memory I will try to keep most secret from the world. Right now I feel there is only one person (E. Boesen) with whom I can really talk about him. He was a "faithful friend." [26]

Regine Olsen and graduation (1837–1841)

An important aspect of Kierkegaard's life, one generally considered to have had a major influence on his work, was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen (1822–1904). Kierkegaard and Olsen met on 8 May 1837 and were instantly attracted but by 11 August 1838 he had second thoughts. In his journals, Kierkegaard wrote about his love for her: "You, sovereign queen of my heart, "Regina, hidden in the deepest secrecy of my breast, in the fullness of my life-idea, there where it is just as far to heaven as to hell — unknown divinity! O, can I really believe the poets when they say that the first time one sees the beloved object he thinks he has seen her long before, that love like all knowledge is recollection, that love in the single individual also has its prophecies, its types, its myths, its Old Testament. Everywhere, in the face of every girl, I see features of your beauty, but I think I would have to possess the beauty of all the girls in the world to extract your beauty, that I would have to sail around the world to find the portion of the world I want and toward which the deepest secret of my self polarically points — and in the next moment you are so close to me, so present, so overwhelmingly filling my spirit that I am transfigured to myself and feel that here it is good to be. You blind god of erotic love! You who see in secret, will you disclose it to me? Will I find what I am seeking here in this world, will I experience the conclusion of all my life's eccentric premises, will I fold you in my arms, or: Do the Orders say: March on? Have you gone on ahead, you, my longing, transfigured do you beckon to me from another world? O, I will throw everything away in order to become light enough to follow you."[27]

On May 13, 1839 Kierkegaard wrote, "I have no alternative than to suppose that it is God's will that I prepare for my examination and that it is more pleasing to him that I do this than actually coming to some clearer perception by immersing myself in one or another sort of research, for obedience is more precious to him than the fat of rams."[28] The death of Poul Moller also played a part in his decision.

On 8 September 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Olsen. However, Kierkegaard soon felt disillusioned about the prospects of the marriage. He broke off the engagement on 11 August 1841, though it is generally believed that the two were deeply in love. In his journals, Kierkegaard mentions his belief that his "melancholy" made him unsuitable for marriage, but his precise motive for ending the engagement remains unclear.[18][29] However, the following quote from his Journals sheds some light on the motivation. "..... and this terrible restlessness — as if wanting to convince myself every moment that it would still be possible to return to her — O God, would that I dared to do it. It is so hard; my last hope in life I had placed in her, and I must deprive myself of it. How strange, I had never really thought of getting married, but I never believed that it would turn out this way and leave so deep a wound. I have always ridiculed those who talked about the power of women, and I still do, but a young, beautiful, soulful girl who loves with all her mind and all her heart, who is completely devoted, who pleads — how often I have been close to setting her love on fire, not to a sinful love, but I need merely have said to her that I loved her, and everything would have been set in motion to end my young life. But then it occurred to me that this would not be good for her, that I might bring a storm upon her head, since she would feel responsible for my death. I prefer what I did do; my relationship to her was always kept so ambiguous that I had it in my power to give it any interpretation I wanted to. I gave it the interpretation that I was a deceiver. Humanly speaking, that is the only way to save her, to give her soul resilience. My sin is that I did not have faith, faith that for God all things are possible, but where is the borderline between that and tempting God; but my sin has never been that I did not love her. If she had not been so devoted to me, so trusting, had not stopped living for herself in order to live for me — well, then the whole thing would have been a trifle; it does not bother me to make a fool of the whole world, but to deceive a young girl. — O, if I dared return to her, and even if she did not believe that I was false, she certainly believed that once I was free I would never come back. Be still, my soul, I will act firmly and decisively according to what I think is right. I will also watch what I write in my letters. I know my moods. But in a letter I cannot, as when I am speaking, instantly dispel an impression when I detect that it is too strong."[30]

On September 29, 1841, Kierkegaard wrote and defended his dissertation, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, which was found by the university panel to be a noteworthy and well-thought out work, but too informal and witty for a serious academic thesis.[31] He graduated from university on 20 October 1841 with a Magister Artium, which today would be designated a Ph.D. With his family's inheritance of approximately 31,000 rigsdaler, Kierkegaard was able to fund his education, his living, and several publications of his early works.[32]

First authorship and Corsair affair (1841–1846)

Kierkegaard's first book, Johannes Climacus, or de omnibus dubitandum est, which means "Everything must be doubted", was written in 1841-42 but was never published until after his death. [33] Although Kierkegaard wrote a few articles on politics, women, and entertainment in his youth and university days, many scholars, such as Alastair Hannay and Edward Mooney, believe Kierkegaard's first noteworthy work is either his university thesis, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, which was presented in 1841, or his masterpiece and arguably greatest work, Either/Or, which was published in 1843.[29][34] Both works treated major figures in Western thought (Socrates in the former and, less directly, Hegel and Friedrich von Schlegel in the latter), and showcased Kierkegaard's unique style of writing. Either/Or was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin and was completed in the autumn of 1842.[34] Kierkegaard ended Either/Or with the words "only the truth that builds up is truth for you." [35] Either/Or was published February 20, 1843 then Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, and Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843. These discourses were published under his own name rather than a pseudonym. He continued to publish discourses, which were written from the Christian point of view, until after completing The Concept of Anxiety. The discourses were discussed in relation to Either/Or in Kierkekgaard's book The Point of View of My Work as an Author and in his Journal entries.

In the same year Either/Or was published, Kierkegaard found out Regine Olsen was engaged to be married to Johan Frederik Schlegel (1817–1896), a civil servant. This fact affected Kierkegaard and his subsequent writings deeply. In Fear and Trembling, a discourse on the nature of faith published in late 1843, one can interpret a section in the work as saying, "Kierkegaard hopes that through a divine act, Regine would return to him."[36] Repetition, published on the very same day as Fear and Trembling and Three Upbuilding Discourses (October 16, 1843), is an exploration of love, religious experience and language reflected in a series of stories about a young gentleman leaving his beloved. Several other works in this period make similar overtones of the Kierkegaard–Olsen relationship.[36] After completing Repetition he wrote Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1844, and Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1844.

Other major works in this period include critiques of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and form a basis for existential psychology. Philosophical Fragments, The Concept of Anxiety, Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844, Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions, and Stages on Life's Way include observations about existential choices and their consequences, and what religious life can mean for a modern individual. Perhaps the most valiant attack on Hegelianism is the Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments which discusses the importance of the individual, subjectivity as truth, and countering the Hegelian claim that "The Rational is the Real and the Real is the Rational".[37]

Many of the works in this authorship were written using a pseudonym and indirectly, representing ways in which individuals find the meaning of life in ethics,[38] power, sorrow,[39] duty,[40] wealth, health, beauty, talent,[41] the erotic;[42] by the accidental, fortunate, unfortunate circumstance,[43] and chance.[44] These individuals can only acquire these goods by getting them from somewhere outside of themselves. However, Kierkegaard published Christian discourses, written under his own name, alongside each pseudonymous work.[45] Kierkegaard's discourses make an appeal to the Christian reader and present in a religious context many of the same themes treated by his pseudonyms.[46] All of Kierkegaard's discourses speak about the Fruit of the Holy Spirit as goods that are comparable to the goods of the world listed above. There's nothing wrong with relative goals, but, don't forget to love your neighbor while pursuing them, don't give up your peace to get them.[47]

You are outside yourself and therefore cannot do without the other as opposition; you believe that only a restless spirit is alive, and all who are experienced believe that only a quiet spirit is truly alive. For you a turbulent sea is a symbol of life; for me it is the quiet, deep water. Either/Or II p. 144 Hong

On 22 December 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller, a young author of Kierkegaard's generation who studied at the University of Copenhagen at the same time as Kierkegaard, published an article indirectly criticising Stages on Life's Way. The article complimented Kierkegaard for his wit and intellect, but questioned whether he would ever be able to master his talent and write coherent, complete works. Møller was also a contributor to and editor of The Corsair, a Danish satirical paper that lampooned everyone of notable standing. Kierkegaard published a sarcastic response, charging that Møller's article was merely an attempt to impress Copenhagen's literary elite. Kierkegaard's article earned him the ire of the paper and its second editor, also an intellectual Kierkegaard's own age, Meïr Aron Goldschmidt.[48]

Kierkegaard wrote two small pieces in response to Møller, The Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action. The former focused on insulting Møller's integrity while the latter was a directed assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard, after criticizing the journalistic quality and reputation of the paper, openly asked The Corsair to satirize him.[49] Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his offer to "be abused", and unleashed a series of attacks making fun of Kierkegaard's appearance, voice, and habits. For months, Kierkegaard perceived himself to be the victim of harassment on the streets of Denmark. In a journal entry dated March 9, 1846, Kierkegaard made a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explained that this attack made him rethink his strategy of indirect communication. In addition, Kierkegaard felt satisfied with his writing so far, and intended to focus on becoming a priest.[32]

Second authorship (1846–1853)

However, Kierkegaard began to write again, and where his first authorship focused on Hegel, this authorship focused on the hypocrisy of Christendom.[51] By Christendom Kierkegaard meant not Christianity itself, but rather the State Church and the applied religion of his society. His first work in this period of his life was Two Ages: A Literary Review which was a critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd.

After giving his critique of the story, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on the nature of the present age and its passionless attitude towards life. One of his complaints about modernity is its passionless view of the world. Kierkegaard writes that "the present age is essentially a sensible age, devoid of passion [...] The trend today is in the direction of mathematical equality, so that in all classes about so and so many uniformly make one individual".[52] In this, Kierkegaard attacks the conformity and assimilation of individuals into an indifferent public, "the crowd".[53] Although Kierkegaard attacks the public, he is supportive of communities where individuals keep their diversity and uniqueness.

Other works continue to focus on the superficiality of "the crowd" attempting to limit and stifle the single individual. The Book on Adler is a work about Pastor Adolph Peter Adler's claim to have had a sacrilegious revelation and to have suffered ostracism and expulsion from the pastorate as a consequence. According to biographer Walter Lowrie, Kierkegaard experienced similar social exclusion which actually brought him closer to his father.[54]

As part of his analysis of the "crowd", Kierkegaard accused the newspapers of decay and decadence. This work is titled: On the Dedication to "That Single Individual" and it is the only work by him that is in the public domain (2010).[55] Kierkegaard also believed Christendom had "lost its way" on the Christian faith. Kiergekaard says, "to recognize "the crowd" as the court of last resort in relation to "the truth," that is to deny God and cannot possibly be to love "the neighbor." ... never have I read in the Holy Scriptures this command: You shall love the crowd; even less: You shall, ethico-religiously, recognize in the crowd the court of last resort in relation to "the truth."[56] According to him, Christendom in this period ignored, skewed, or gave mere 'lip service' to the original Christian doctrine. Kierkegaard felt it his duty throughout his works to inform others about what he considered the shallowness of so-called "Christian living". He wrote several works on contemporary Christianity such as Christian Discourses, Works of Love, and Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits[29], which included Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing.

The Sickness Unto Death is one of Kierkegaard's most popular works of this era among philosophers, and although some contemporary atheistic philosophers and psychologists dismiss Kierkegaard's suggested solution as faith, his analysis on the nature of despair is one of the best accounts on the subject and has been emulated in subsequent philosophies, such as Heidegger's concept of existential guilt and Sartre's bad faith. Four months after publishing this book he wrote Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays. Around 1848, Kierkegaard began openly presenting his case for Christianity to the "Single Individual" with Practice in Christianity, For Self-Examination, Judge for Yourselves!, and The Point of View of My Work as an Author. His hope was that someone would take notice.[57][58]

In 1847, Regine Olsen, Kierkegaard's former fiancée, and Frederik Schlegel were married. On several occasions in 1849, she and Kierkegaard crossed paths on the streets of Copenhagen. Kierkegaard wrote to her husband, asking for permission to speak to her, but Schlegel refused. Soon afterwards, the couple left the country, Schlegel having been appointed Governor General of the Danish West Indies. By the time they returned, Kierkegaard was dead. A few years before his death, Kierkegaard stated in his will that she should inherit his estate, and all his authorial activity was dedicated to her. Regine Schlegel lived until 1904 and was buried near Kierkegaard in the Assistens Cemetery in Copenhagen.[17]

Attack upon the Church (1854–1855)

Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Danish National Church by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment (Øjeblikket).[59] Kierkegaard was initially called to action after Professor Hans Lassen Martensen gave a speech in church in which he called his recently deceased predecessor Bishop Jakob P. Mynster a "truth-witness, one of the authentic truth-witnesses."[7] He explained, in the first article, that the death of this person permitted him - at last - to be frank about his opinions. Later during the campaign he directly wrote that all his former writings had been "preparations" for this final attack postponed for years for two reasons: 1. Both his father and bishop Mynster should be dead before the attack and 2. he should himself have acquired a name as a famous theologic writer.[60] During the ten issues of Øjeblikket the aggressivity of the language increased and the “thousand danish priests“ “playing christianity“ were finally called “man-eaters“ after having been “liars“, “hypocrites“ and “destroyers of christianity" in the first issues. This verbal violence gave a gigantic echo in Denmark, but today Kierkegaard is often considered to have lost control of himself during this campaign.[61].

There is really a deceptive turn by Bishop Mynster when in his sermons (the one on "Give us this day our daily bread" and the one on miracles) he says concerning the forgiveness of sin: Some day (that is, in eternity) it shall be said to him who in repentance has humbled himself and believed, "Your sins are forgiven you." "Some day," i.e., in eternity — but the nub of the forgiveness of sin is precisely to make it valid in time. It is the new creation, and the pastor does say at confession: "I declare unto you the gracious forgiveness of all your sins." Is this forgiveness only for the future? Once again this is using immanence (this some day) instead of transcendence. Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard VII 1A 78

The father of Kierkegaard had been a close friend of Mynster, but Søren had since long come to see that Mynster's conception of Christianity was mistaken and demanded too little of its adherents. Kierkegaard believed that, in no way, was Mynster's life comparable to that of a real 'truth-witness'. Before the tenth issue of his periodical The Moment could be published, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street and was eventually taken to a hospital. He stayed in the hospital for over a month and refused to receive communion from a pastor. At that time Kierkegaard regarded the pastor as a mere political official with a niche in society who was clearly not representative of the divine. He said to Emil Boesen, a friend since childhood who kept a record of his conversations with Kierkegaard, that his life had been one of immense suffering, which may have seemed like vanity to others, but he did not think it so.[29]

Kierkegaard died in Frederik's Hospital after being there for over a month, possibly from complications from a fall he had taken from a tree in his youth. He was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen. At Kierkegaard's funeral, his nephew Henrik Lund caused a disturbance by protesting the burying of Kierkegaard by the official church. Lund maintained that Kierkegaard would never have approved, had he been alive, as he had broken from and denounced the institution. Lund was later fined for his public disruption of a funeral.[18]

Thought

Kierkegaard has been called a philosopher, a theologian,[62] the Father of Existentialism, both atheistic and theistic variations,[63] a literary critic,[53] a social theorist,[64] a humorist,[65] a psychologist,[8] and a poet.[66] Two of his popular ideas are "subjectivity",[67] and the notion popularly referred to as "leap of faith".[2][68]

The leap of faith is his conception of how an individual would believe in God or how a person would act in love. Faith is not a decision based on evidence that, say, certain beliefs about God are true or a certain person is worthy of love. No such evidence could ever be enough to pragmatically justify the kind of total commitment involved in true religious faith or romantic love. Faith involves making that commitment anyway. Kierkegaard thought that to have faith is at the same time to have doubt. So, for example, for one to truly have faith in God, one would also have to doubt one's beliefs about God; the doubt is the rational part of a person's thought involved in weighing evidence, without which the faith would have no real substance. Someone who does not realize that Christian doctrine is inherently doubtful and that there can be no objective certainty about its truth does not have faith but is merely credulous. For example, it takes no faith to believe that a pencil or a table exists, when one is looking at it and touching it. In the same way, to believe or have faith in God is to know that one has no perceptual or any other access to God, and yet still has faith in God.[69] As Kierkegaard writes, "doubt is conquered by faith, just as it is faith which has brought doubt into the world".[70][71]

Kierkegaard also stressed the importance of the self, and the self's relation to the world, as being grounded in self-reflection and introspection. He argued in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity." This has to do with a distinction between what is objectively true and an individual's subjective relation (such as indifference or commitment) to that truth. People who in some sense believe the same things may relate to those beliefs quite differently. Two individuals may both believe that many of those around them are poor and deserve help, but this knowledge may lead only one of them to decide to actually help the poor.[72]

Kierkegaard primarily discusses subjectivity with regard to religious matters, however. As already noted, he argues that doubt is an element of faith and that it is impossible to gain any objective certainty about religious doctrines such as the existence of God or the life of Christ. The most one could hope for would be the conclusion that it is probable that the Christian doctrines are true, but if a person were to believe such doctrines only to the degree they seemed likely to be true, he or she would not be genuinely religious at all. Faith consists in a subjective relation of absolute commitment to these doctrines.[73]

Pseudonymous authorship

Half of Kierkegaard's authorship was written under pseudonyms which represented different ways of thinking. Pseudonyms were used often in the early 1800's, other examples include the writers of the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers. Kierkegaard used the same technique. Some scholars think this was part of Kierkegaard's theory of "indirect communication." According to several passages in his works and journals, such as The Point of View of My Work as an Author, Kierkegaard wrote this way in order to prevent his works from being treated as a philosophical system with a systematic structure. In the Point of View, Kierkegaard wrote: "The movement: from the poet (from aesthetics), from philosophy (from speculation), to the indication of the most central definition of what Christianity is-from the pseudonymous ‘Either/Or’, through ‘The Concluding Postscript’ with my name as editor, to the ‘Discourses at Communion on Fridays’, two of which were delivered in the Church of our Lady. This movement was accomplished or described uno tenore, in one breath, if I may use this expression, so that the authorship integrally regarded, is religious from first to last-a thing which everyone can see if he is willing to see, and therefore ought to see. "[74] and "That even if a man will not follow where one endeavors to lead him, one thing it is still possible to do for him-compel him to take notice. One man may have the good fortune to do much for another, he may have the good fortune to lead him whither he wishes, and (to stick to the subject which here is our constant and essential interest) he may have the good fortune to help him to become a Christian. But this result is not in my power; it depends upon so many things, and above all it depends upon whether he will or no. In all eternity it is impossible for me to compel a person to accept an opinion, a conviction, a belief. But one thing I can do: I can compel him to take notice. In one sense this is the first thing; for it is the condition antecedent to the next thing, i.e. the acceptance of an opinion, a conviction, a belief. In another sense it is the last-if, that is, he will not take the next step." [75][76]

He hoped readers would simply read the work at face value without attributing it to some aspect of his life. Kierkegaard also did not want his readers to treat his work as an authoritative system, but rather look to themselves for interpretation.[77]

Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno and Thomas Henry Croxall, have respected Kierkegaard's intentions and argue the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views.[78] This view leads to many confusions and contradictions which make Kierkegaard appear incoherent from the philosophical point of view.[79] Many later scholars, such as the post-structuralists, have interpreted Kierkegaard's work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors.[80] Kierkegaard uses the category of "The Individual"[81] to stop[82] the endless Either/Or. [83]

Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms,[84] in chronological order, are:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or

- A, writer of many articles in Either/Or

- Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either/Or

- Johannes de silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Constantin Constantius, author of the first half of Repetition

- Young Man, author of the second half of Repetition

- Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Anxiety

- Nicolaus Notabene, author of Prefaces

- Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

- Inter et Inter, author of The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress

- H.H., author of Two Ethical-Religious Essays

- Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness Unto Death and Practice in Christianity

... As is well-known, my authorship has two parts: one pseudonymous and the other signed. The pseudonymous writers are poetic creations, poetically maintained so that everything they say is in character with their poetized individualized personalities; sometimes I have carefully explained in a signed preface my own interpretation of what the pseudonym said. Anyone with just a fragment of common sense will perceive that it would be ludicrously confusing to attribute to me everything the poetized characters say. Nevertheless, to be on the safe side, I have expressed urged that anyone who quotes something from the pseudonyms will not attribute the quotation to me (see my postscript to Concluding Postscript). It is easy to see that anyone wanting to have a literary lark merely needs to take some verbatim quotations from "The Seducer," then from Johannes Climacus, then from me, etc., print them together as if they were all my words, show how they contradict each other, and create a very chaotic impression, as if the author were a kind of lunatic. Hurrah! That can be done. In my opinion anyone who exploits the poetic in me by quoting the writings in a confusing way is more or less a charlatan or a literary toper. Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard X 6 b 145 1851

Journals

People understand me so little that they do not even understand when I complain of being misunderstood. Journals Feb. 1836

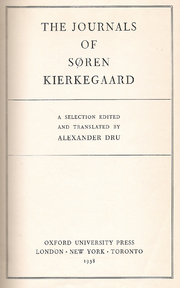

Kierkegaard's journals are essential to understanding him and his work. Samuel Hugo Bergmann wrote, "Kierkegaard journal's are one of the most important sources for an understanding of his philosophy".[85] Kierkegaard wrote over 7000 pages in his journals describing key events, musings, thoughts about his works and everyday remarks.[86] The entire collection of Danish journals has been edited and published in 13 volumes which consist of 25 separate bindings including indices. The first English edition of the journals was edited by Alexander Dru in 1938.[32] His journals reveal many different facets of Kierkegaard and his work and help elucidate many of his ideas. The style in his journals is written in "literary and poetic manner".[87] Kierkegaard took his journals seriously and even once wrote that they were his most trusted confidant:

I have never confided in anyone. By being an author I have in a sense made the public my confidant. But in respect of my relation to the public I must, once again, make posterity my confidant. The same people who are there to laugh at one cannot very well be made one's confidant.[88]—Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, p. 221 (4 November 1847)

His journals are also the source of many aphorisms credited to Kierkegaard. The following passage is perhaps the most oft-quoted aphorism from Kierkegaard's journals and is usually a key quote for existentialist studies: "The thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live and die."[89] It was written on 1 August 1835. Although his journals clarify some aspects of his work and life, Kierkegaard took care not to reveal too much. Abrupt changes in thought, repetitive writing, and unusual turns of phrase are some among the many tactics he uses to throw readers off track. Consequently, there are many varying interpretations of his journals. However, Kierkegaard did not doubt the importance his journals would have in the future. In a journal entry in December 1849, he wrote: "Were I to die now the effect of my life would be exceptional; much of what I have simply jotted down carelessly in the Journals would become of great importance and have a great effect; for then people would have grown reconciled to me and would be able to grant me what was, and is, my right."[90]

… when I have encountered something in life, when I have decided on something that I was afraid would take on another aspect for me in the course of time, when I have done something I was afraid I would interpret differently in the course of time, I often wrote down briefly and clearly what it was that I wanted or what it was that I had done and why. Then when I felt that I needed it, when my decision or my action was not vivid to me, I would take out my charter and judge myself. Either/Or Vol II 1843 Hong P. 197

Kierkegaard and Christianity

As mentioned above, Kierkegaard took up a sustained attack on the official kind of Christendom, or Christianity as a political entity, during the final years of his life. In the 19th century, most Danes who were citizens of Denmark were necessarily members of the Danish National Church. Kierkegaard felt this state-church union was unacceptable and perverted the true meaning of Christianity.[7]

In Kierkegaard's pamphlets and polemical books, including The Moment, he criticized several aspects of church formalities and politics.[91] According to Kierkegaard, the idea of congregations keeps individuals as children since Christians are disinclined from taking the initiative to take responsibility for their own relation to God. He stresses that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual."[92] Furthermore, since the Church was controlled by the State, Kierkegaard believed the State's bureaucratic mission was to increase membership and oversee the welfare of its members. More members would mean more power for the clergymen: a corrupt ideal.[93] This mission would seem at odds with Christianity's true doctrine, which, to Kierkegaard, is to stress the importance of the individual, not the whole.[32] Thus, the state-church political structure is offensive and detrimental to individuals, since anyone can become "Christian" without knowing what it means to be Christian. It is also detrimental to the religion itself since it reduces Christianity to a mere fashionable tradition adhered to by unbelieving "believers", a "herd mentality" of the population, so to speak.[94] In the Journals, Kierkegaard writes:

If the Church is "free" from the state, it's all good. I can immediately fit in this situation. But if the Church is to be emancipated, then I must ask: By what means, in what way? A religious movement must be served religiously—otherwise it is a sham! Consequently, the emancipation must come about through martyrdom—bloody or bloodless. The price of purchase is the spiritual attitude. But those who wish to emancipate the Church by secular and worldly means (i.e. no martyrdom), they've introduced a conception of tolerance entirely consonant with that of the entire world, where tolerance equals indifference, and that is the most terrible offence against Christianity. [...] the doctrine of the established Church, its organization, are both very good indeed. Oh, but then our lives: believe me, they are indeed wretched.[95]—Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, p.429 (January 1851)

Attacking what he considered the incompetence and corruption of the Christian churches, Kierkegaard seemed to have anticipated philosophers like Nietzsche who would go on to criticize the Christian religion itself.[96]

I ask: what does it mean when we continue to behave as though all were as it should be, calling ourselves Christians according to the New Testament, when the ideals of the New Testament have gone out of life? The tremendous disproportion which this state of affairs represents has, moreover, been perceived by many. They like to give it this turn: the human race has outgrown Christianity.—Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, p.446[32] (19 June 1852)

Criticism

Some of Kierkegaard's famous philosophical critics in the 20th century include Theodor Adorno and Emmanuel Levinas. Atheistic philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and agnostic philosophers like Martin Heidegger support many aspects of Kierkegaard's philosophical views, but criticize and reject some of his religious views.[97][98]

Several Kierkegaardian scholars argue Adorno's take on Kierkegaard's philosophy has been less than faithful to the original intentions of Kierkegaard. One critic of Adorno writes that his book Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic is "the most irresponsible book ever written on Kierkegaard"[99] because Adorno takes Kierkegaard's pseudonyms literally, and constructs an entire philosophy of Kierkegaard which makes him seem incoherent and unintelligible. Another reviewer says that "Adorno is [far away] from the more credible translations and interpretations of the Collected Works of Kierkegaard we have today."[79]

Levinas' main attack on Kierkegaard is focused on his ethical and religious stages, especially in Fear and Trembling. Levinas criticises the leap of faith by saying this suspension of the ethical and leap into the religious is a type of violence.

Kierkegaardian violence begins when existence is forced to abandon the ethical stage in order to embark on the religious stage, the domain of belief. But belief no longer sought external justification. Even internally, it combined communication and isolation, and hence violence and passion. That is the origin of the relegation of ethical phenomena to secondary status and the contempt of the ethical foundation of being which has led, through Nietzsche, to the amoralism of recent philosophies.—Emmanuel Levinas, Existence and Ethics, (1963)[100]

Levinas points to the Judeo-Christian belief that it was God who first commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and that it was an angel who commanded Abraham to stop. If Abraham were truly in the religious realm, he would not have listened to the angel to stop and should have continued to kill Isaac. "Transcending ethics" seems like a loophole to excuse would-be murders from their crime and thus is unacceptable.[101] One interesting consequence of Levinas' critique is that it seems to reveal that Levinas views God not as an absolute moral agent but as a projection of inner ethical desire.[102]

On Kierkegaard's religious views, Sartre offers this argument against existence of God: If existence precedes essence, it follows from the meaning of the term sentient that a sentient being cannot be complete or perfect. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre's phrasing is that God would be a pour-soi [a being-for-itself; a consciousness] who is also an en-soi [a being-in-itself; a thing]: which is a contradiction in terms.[97][103]

Sartre agrees with Kierkegaard's analysis of Abraham undergoing anxiety (Sartre calls it anguish), but Sartre doesn't agree that God told him to do it. In his lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism, Sartre wonders if Abraham ought to have doubted whether God actually spoke to him or not.[97] In Kierkegaard's view, Abraham's certainty had its origin in that 'inner voice' which cannot be demonstrated or shown to another ("The problem comes as soon as Abraham wants to be understood"). To Kierkegaard, every external "proof" or justification is merely on the outside and external to the subject.[104] Kierkegaard's proof for the immortality of the soul, for example, is rooted in the extent to which one wishes to live forever.[105]

Influence and reception

Kierkegaard's works were not widely available until several decades after his death, however, in 1855, the Danish National Church did publish his obituary[106]. The obscurity of the Danish language, relative to German, French, and English, made it nearly impossible for Kierkegaard to acquire non-Danish readers. Several early writers wondered why he wasn't translated into English, H. R. Mackintosh[107] and C.H.A Bjerregaard[108] since he was such an excellent writer. Hans Martinsen did write a monograph about Kierkegaard in 1856, a year after his death, Dr. S. Kierkegaard mod Dr. H. Martensen: et indlaeg[109] but it hasn't been translated into English and mentioned him in Christian Ethics[110] (1871) as did Otto Pfleiderer in The Philosophy of Religion: On the Basis of Its History[111] (1887) , The dramatist Henrik Ibsen became interested in Kierkegaard and introduced his work to the rest of Scandinavia. During the 1890s, Japanese philosophers began disseminating the works of Kierkegaard, from the Danish thinkers.[112] Tetsuro Watsuji was one of the first philosophers outside of Scandinavia to write an introduction on the philosophy of Kierkegaard in 1915. Harald Høffding has an article about him in A brief history of modern philosophy[113] (1900). The Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics[114] had an acticle about him in (1908). David F. Swenson wrote a biography of Soren Kierkegaard (1921). He said,

It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world. Soren Kierkegaard p.41

The first academic to draw attention to Kierkegaard was his fellow Dane Georg Brandes, who published in German as well as Danish. Brandes gave the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard in Copenhagen and helped bring Kierkegaard to the attention of the rest of the European intellectual community.[115] Brandes published the first book on Kierkegaard's philosophy and life. Sören Kierkegaard, ein literarisches Charakterbild. Autorisirte deutsche Ausg (1879)[116] and compared him to Hegel in Reminiscences of my Childhood and Youth[117] (1906). He also introduced Friedrich Nietzsche to Europe in 1915 by writing a biography about him.[118] Brandes opposed Kierkegaard's ideas.[119] Kierkegaard's main works were translated into German by Christoph Schrempf from 1909 onwards,[120] a German edition of Kierkegaard's collected works was done by Emmanuel Hirsch from 1950 on.[120] Kierkegaard's comparatively early and manifold philosophical and theological reception in Germany was one of the decisive factors of expanding his works, influence, and readership throughout the world.[121][122]

Important for the first phase of his reception in Germany was the establishment of the journal Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Ages) in 1922 by a heterogeneous circle of Protestant theologians: Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Rudolf Bultmann and Friedrich Gogarten.[123] Their thought would soon be referred to as dialectical theology.[123] Roughly at about the same time, Kierkegaard was discovered by several proponents of the Jewish-Christian philosophy of dialogue in Germany,[124] namely by Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner, and Franz Rosenzweig.[125] In addition to the philosophy of dialogue, existential philosophy has its point of origin in Kierkegaard and his concept of individuality.[126] Martin Heidegger sparsely refers to Kierkegaard in Being and Time (1927),[127] obscuring how much he owes to him.[128][129][130] In 1935, Karl Jaspers emphasized Kierkegaard's (and Nietzsche's) continuing importance for modern philosophy.[131] Walter Kaufmann discussed Sartre, Jaspers, and Heideggers in relation to Kierkegaard and Kierkegaard in relation to the crisis of religion. 1960[132]

In the 1930s, the first academic English translations,[133] by Alexander Dru, David F. Swenson, Douglas V. Steere, and Walter Lowrie appeared, under the editorial efforts of Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams.[2] Thomas Henry Croxall, another early translator, Lowrie, and Dru all hoped that people would not just read about Kierkegaard but would go on and actually read his works.[134] The second and currently widely used academic English translations were published by the Princeton University Press in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, under the supervision of Howard V. Hong. A third official translation, under the aegis of the Søren Kierkegaard Research Center, will extend to 55 volumes and is expected to be completed sometime after 2009.[135]

Many 20th-century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, and theologians drew many concepts from Kierkegaard, including the notions of angst, despair, and the importance of the individual. His fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, in large part because the ascendant existentialist movement pointed to him as a precursor, although he is now seen as a highly significant and influential thinker in his own right.[136] As Kierkegaard was raised as a Lutheran,[137] he is commemorated as a teacher in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 11 November and in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 8 September.

Philosophers and theologians influenced by Kierkegaard include Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Barth, Simone de Beauvoir, Niels Bohr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Emil Brunner, Martin Buber, Rudolf Bultmann, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Reinhold Niebuhr, Franz Rosenzweig, Jean-Paul Sartre, Joseph Soloveitchik, Paul Tillich, Miguel de Unamuno. Paul Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism was inspired by Kierkegaard's idea of subjectivity as truth. Ludwig Wittgenstein was immensely influenced and humbled by Kierkegaard,[13] claiming that "Kierkegaard is far too deep for me, anyhow. He bewilders me without working the good effects which he would in deeper souls".[13] Karl Popper referred to Kierkegaard as "the great reformer of Christian ethics, who exposed the official Christian morality of his day as anti-Christian and anti-humanitarian hypocrisy".[138]

The comparison between Nietzsche and Kierkegaard that has become customary, but is no less questionable for that reason, fails to recognize, and indeed out of a misunderstanding of the essence of thinking, that Nietzsche as a metaphysical thinker preserves a closeness to Aristotle. Kierkegaard remains essentially remote from Aristotle, although he mentions him more often. For Kierkegaard is not a thinker but a religious writer, and indeed not just one among others, but the only one in accord with the destining belonging to his age. Therein lies his greatness, if to speak in this way is not already a misunderstanding. Heidegger: Nietzsche's Word, "God is Dead." P. 94

Contemporary philosophers such as Emmanuel Lévinas, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Jacques Derrida, Jürgen Habermas, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Richard Rorty, although sometimes highly critical, have also adapted some Kierkegaardian insights.[139][140][141] Hilary Putnam admires Kierkegaard, "for his insistence on the priority of the question, 'How should I live?'".[142]

Kierkegaard has also had a considerable influence on 20th-century literature. Figures deeply influenced by his work include W. H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka,[143] David Lodge, Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Rainer Maria Rilke, J.D. Salinger and John Updike.[144]

Kierkegaard also had a profound influence on psychology and is more or less the founder of Christian psychology[145] and of existential psychology and therapy.[8] Existentialist (often called "humanistic") psychologists and therapists include Ludwig Binswanger, Viktor Frankl, Erich Fromm, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May. May based his The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard's sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age provides an interesting critique of modernity.[53] Kierkegaard is also seen as an important precursor of postmodernism.[139] In popular culture, he has been the subject of serious television and radio programmes; in 1984, a six-part documentary Sea of Faith: Television series presented by Don Cupitt featured a programme on Kierkegaard, while on Maundy Thursday in 2008, Kierkegaard was the subject of discussion of the BBC Radio 4 programme presented by Melvyn Bragg, In Our Time.

Kierkegaard predicted his posthumous fame, and foresaw that his work would become the subject of intense study and research. In his journals, he wrote:

What the age needs is not a genius—it has had geniuses enough, but a martyr, who in order to teach men to obey would himself be obedient unto death. What the age needs is awakening. And therefore someday, not only my writings but my whole life, all the intriguing mystery of the machine will be studied and studied. I never forget how God helps me and it is therefore my last wish that everything may be to his honour.[146]—Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, p.224 (20 November 1847)

Selected bibliography

For a complete bibliography, see List of works by Søren Kierkegaard

- (1841) On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates (Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt Hensyn til Socrates)

- (1843) Either/Or (Enten-Eller)

- (1843) Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- (1843) Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- (1843) Fear and Trembling (Frygt og Bæven)

- (1843) Repetition (Gjentagelsen)

- (1843) Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843

- (1844) Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1844)

- (1844) Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1844)

- (1844) Philosophical Fragments (Philosophiske Smuler)

- (1844) The Concept of Anxiety (Begrebet Angest)

- (1844) Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844)

- (1845) Stages on Life's Way (Stadier paa Livets Vei)

- (1846) Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments (Afsluttende uvidenskabelig Efterskrift)

- (1847) Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits (Opbyggelige Taler i forskjellig Aand)

- (1847) Works of Love (Kjerlighedens Gjerninger)

- (1848) Christian Discourses (Christelige Taler)

- (1848) The Point of View of My Work as an Author "as good as finished" (IX A 293)

- (1849) The Sickness Unto Death (Sygdommen til Døden)

- (1849) Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays

- (1850) Practice in Christianity (Indøvelse i Christendom)

Notes

- ↑ This classification is anachronistic; Kierkegaard was an exceptionally unique thinker and his works do not fit neatly into any one philosophical school or tradition, nor did he identify himself with any. However, his works are considered precursor to many schools of thought developed in the 20th and 21st centuries. See 20th century receptions in Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 (Hannay & Marino, 1997)

- ↑ The influence of Socrates can be seen in Kierkegaard's Sickness Unto Death and Works of Love.

- ↑ 1911 Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica/Soren Kierkegaard

- ↑ (Gardiner, 1969)

- ↑ Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments Hong p. 15-17, 555-610 Either/Or II p. 14, 58, 216-217, 250 Hong

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 (Duncan, 1976)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 (Ostenfeld & McKinnon, 1972)

- ↑ (Howland, 2006)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1976, p. 303)

- ↑ (Hubben, 1962)

- ↑ (Lippitt & Hutto, 1998)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 (Creegan, 1989)

- ↑ Johannes Climacus, by Soren Kierkegaard p. 17

- ↑ See David F. Swenson's 1921 biography of SK, p. 2, 13

- ↑ Concluding Unscientific Postscript p. 72ff Hong

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 (Watkin, 2000)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 (Garff, 2005)

- ↑ Johannes Climacus, by Soren Kierkegaard p. 29

- ↑ Kierkegaard's Journals Gilleleie, August 1, 1835 Either/Or Vol II p. 361-362

- ↑ Johannes Climacus, by Soren Kierkegaard p. 22-23, 29-30, p. 32-33, 67-70, 74-76

- ↑ Point of View Lowrie 28-30

- ↑ Johannes Climacus, by Soren Kierkegaard p. 23

- ↑ Point of View Lowrie p. 89

- ↑ (Garff, 2005, p. 113); Also available in Encounters With Kierkegaard: A Life As Seen by His Contemporaries, p. 225.

- ↑ Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard IIA 11 August 1838

- ↑ Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard IIA 11 August 1838 http://www.naturalthinker.net/trl/texts/Kierkegaard,Soren/JournPapers/II_A.html

- ↑ Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard IIA 11 May 13, 1839

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 (Hannay, 2003)

- ↑ Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard IIIA 166

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1989)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 (Dru, 1938)

- ↑ Johannes Climacus: or. De omnibus dubitandum est, and A sermon. Translated, with an assessment by T. H. Croxall 1958 B 4372 .E5 1958

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 (Mooney, 2007)

- ↑ Either /Or Vol II, Hong p. 354

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 (Lippitt, 2003)

- ↑ (Hegel, 1979)

- ↑ Either/Or II p. 183 Hong

- ↑ Either/Or Vol I Swenson Shadowgraphs p. 173, Vol II p. 235-239 Hong

- ↑ Either/Or II p. 254ff Hong

- ↑ Either/Or II p. 183 Hong

- ↑ Either/Or II p. 141-142 Hong

- ↑ Either/Or Vol I Swenson Immediate Stages of the Erotic p. 45-46

- ↑ Either/Or Vol I Swenson p. 322-323

- ↑ In English, the first of these discourses have been published under the title Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses by Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691020876.

- ↑ (Pattison, 2002)

- ↑ Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, The Expectancy of Faith p. 23-24

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1978, pp. vii–xii)

- ↑ Kierkegaard, Søren. Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action in Essential Kierkegaard.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 (Royal Library of Denmark, 1997)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1978)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 2001, p. 86)

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 (Kierkegaard, 2001)

- ↑ (Lowrie, 1942)

- ↑ The Crowd is Untruth http://www.ccel.org/ccel/kierkegaard/untruth/files/untruth.html

- ↑ The Crowd is Untruth

- ↑ Point of View 1962 Lowrie p. 6-9, 24, 30, 40, 49, 74-77, 89 Concluding Unscientific Postscript 15-16, 607-614

- ↑ (Lowrie, 1968)

- ↑ (Lowrie, 1962)

- ↑ For instance in "Hvad Christus dømmer om officiel Christendom.“ 1855.

- ↑ For instance: In Lindhardt: Vækkelser og Kirkelige Retninger i Danmark. Det Danske Forlag 1951, the attack is coined as “pathological“. And in Danstrup and Koch's Danmarks Historie it is called “sygeligt“ Vol. 11, p.398

- ↑ (Kangas, 1998)

- ↑ (McGrath, 1993, p. 202)

- ↑ (Westphal, 1997)

- ↑ (Oden, 2004)

- ↑ (MacKey, 1971)

- ↑ Kierkegaard is not an extreme subjectivist; he would not reject the importance of objective truths.

- ↑ The Danish equivalent to the English phrase "leap of faith" does not appear in the original Danish nor is the English phrase found in current English translations of Kierkegaard's works. However, Kierkegaard does mention the concepts of "faith" and "leap" together many times in his works. See Faith and the Kierkegaardian Leap in Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard.

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1992, pp. 21–57)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1976, p. 399)

- ↑ Elsewhere, Kierkegaard uses the Faith/Offense dichotomy. In this dichotomy, doubt is the middle ground between faith and taking offense. Offense, in his terminology, describes the threat faith poses to the rational mind. He uses Jesus' words in Matthew 11:6: "And blessed is he, whosoever shall not be offended in me". In Practice in Christianity, Kierkegaard writes: "Just as the concept of "faith" is an altogether distinctively Christian term, so in turn is "offense" an altogether distinctively Christian term relating to faith. The possibility of offense is the crossroad, or it is like standing at the crossroad. From the possibility of offense, one turns either to offense or to faith, but one never comes to faith except from the possibility of offense" (p. 80). In the footnote, he writes, "in the works of some psuedonymous writers it has been pointed out that in modern philosophy there is a confused discussion of doubt where the discussion should have been about despair. Therefore one has been unable to control or govern doubt either in scholarship or in life. "Despair," however, promptly points in the right direction by placing the relation under the rubric of personality (the single individual) and the ethical. But just as there is a confused discussion of "doubt instead of a discussion of "despair, " So also the practice has been to use the category "doubt" where the discussion ought to be about "offense." The relation, the relation of personality to Christianity, is not to doubt or to believe, but to be offended or to believe. All modern philosophy, both ethically, and Christianly, is based upon frivolousness. Instead of deterring and calling people to order by speaking of being despairing and being offended, it has waved to them and invited them to become conceited by doubting and having doubted. Modern philosophy, being abstract, is floating in metaphysical indeterminateness. Instead of explaining this about itself and then directing people (individual persons) to the ethical, the religious, the existential, philosophy has given the appearance that people are able to speculate themselves out of their own skin, as they so very prosaically say, into pure appearance." (Practice in Christianity, trans. Hong 1991, p.80.) He writes that the person is either offended that Christ came as a man, and that God is too high to be a lowly man who is actually capable of doing very little to resist. Or Jesus, a man, thought himself too high to consider himself God (blasphemy). Or the historical offense where God a lowly man comes into collision with an established order. Thus, this offensive paradox is highly resistant to rational thought.

- ↑ (Pattison, 2005)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1992)

- ↑ (The Point of View of My Work as An Author: Lowrie p. 142-143)

- ↑ The Point of View of My Work as An Author: Lowrie p.35

- ↑ See also Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments Volume I, by Johannes Climacus, edited by Soren Kierkegaard, Copyright 1846 – Edited and Translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong 1992 Princeton University Press p. 251-300 for more on the Pseudonymous authorship.

- ↑ (Carlisle, 2006)

- ↑ (Adorno, 1989)

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 (Morgan)

- ↑ (Evans, 1996)

- ↑ POV Lowrie P. 133-134

- ↑ POV Lowrie p. 74-75

- ↑ Either/Or Vol I Swenson, p. 13-14

- ↑ (Malantschuk & Hong, 2003)

- ↑ (Bergmann, 1991, p. 2)

- ↑ Given the importance of the journals, references in the form of (Journals, XYZ) are referenced from Dru's 1938 Journals. When known, the exact date is given; otherwise, month and year, or just year is given.

- ↑ (Conway & Gover, 2002, p.25)

- ↑ (Dru, 1938, p.221)

- ↑ (Dru, 1938, p. 15)

- ↑ (Dru, 1938, p. 354)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1998b)

- ↑ (Kirmmse, 2000)

- ↑ (Walsh, 2009)

- ↑ (Kierkegaard, 1999)

- ↑ (Dru, 1938, p. 429)

- ↑ (Angier, 2006)

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 (Sartre, 1946)

- ↑ (Dreyfus, 1998)

- ↑ (Westphal, 1996, p. 9)

- ↑ (as cited in Lippitt, 2003, p. 136)

- ↑ (Katz, 2001)

- ↑ (Hutchens, 2004)

- ↑ (Sartre, 1969, p. 430)

- ↑ (Stern, 1990)

- ↑ (Kosch, 1997)

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/evangelicalchri03alligoog#page/n565/mode/1up

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/expositorytimes00unkngoog#page/n418/mode/1up

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/concisedictiona00jackgoog#page/n479/mode/1up

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/details/drskierkegaardm00hangoog

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/christianethicsg00mart#page/215/mode/1up S68-70+

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/philosophyrelig08pflegoog#page/n223/mode/1up p.209-213

- ↑ (Masugata, 1999)

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofmodernp02hfuoft#page/282/mode/2up p. 283-289

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/encyclopaediaofr07hastuoft#page/696/mode/1up

- ↑ (Hall, 1983)

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/details/srenkierkegaard00brangoog

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/stream/reminiscencesmy00brangoog#page/n110/mode/1up p. 98-108

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, by George Brandes 1906 not in pd but online

- ↑ 1911 Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica/Soren Kierkegaard

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 (Bösl, 1997, p. 12)

- ↑ (Stewart, 2009)

- ↑ (Bösl, 1997, p. 13)

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 (Bösl, 1997, p. 14)

- ↑ The German Wikipedia has an article on Dialogphilosophie.

- ↑ (Bösl, 1997, p. 16-17)

- ↑ (Bösl, 1997, p. 17)

- ↑ Heidegger, Sein und Zeit, Notes to pages 190, 235, 338

- ↑ (Bösl, 1997, p. 19)

- ↑ (Beck, 1928)

- ↑ (Wyschogrod, 1954)

- ↑ (Jaspers, 1935)

- ↑ Audio recordins of Kaufmann's lectures http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=walter%20kaufmann

- ↑ However, an independent English translation of selections/excerpts of Kierkegaard appeared in 1923 by Lee Hollander, and published by the University of Texas at Austin.

- ↑ Kierkegaard studies, with special reference to (a) the Bible (b) our own age. Thomas Henry Croxall, Published: 1948 p. 16-18

- ↑ (Søren Kierkegaard Forskningscenteret, 2010)

- ↑ (Weston, 1994)

- ↑ (Hampson, 2004)

- ↑ (Popper, 2002)

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 (Matustik & Westphal, 1995)

- ↑ (MacIntyre, 2001)

- ↑ (Rorty, 1989)

- ↑ (Pyle, 1999, p. 52-53)

- ↑ (McGee, 2006)

- ↑ (Updike, 1997)

- ↑ (Society for Christian Psychology)

- ↑ (Dru, 1938, p.224)

References

Book

- Adorno, Theodor W. (1989). Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816611866

- Angier, Tom. (2006). Either Kierkegaard/or Nietzsche: Moral Philosophy in a New Key. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754654745

- Beck, M. (1928). Referat und Kritik von M.Heidegger: Sein und Zeit, in: Philosophische Hefte 1 7 (German)

- Bergmann, Samuel Hugo. (1991). Dialogical philosophy from Kierkegaard to Buber. New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791406236

- Bösl, Anton. (1997). Unfreiheit und Selbstverfehlung. Søren Kierkegaards existenzdialektische Bestimmung von Schuld und Sühne. (German) Herder: Freiburg, Basel, Wien

- Cappelorn, Niels J. (2003). Written Images. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691115559

- Carlisle, Claire. (2006). Kierkegaard: a guide for the perplexed. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826486110

- Conway, Daniel W. and Gover, K. E. (2002). Søren Kierkegaard: critical assessments of leading philosophers. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415235877

- Dreyfus, Hubert. (1998). Being-in-the-World: A Commentary on Heidegger's Being and Time, Division I. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262540568

- Dru, Alexander. (1938). The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Duncan, Elmer. (1976). Søren Kierkegaard: Maker of the Modern Theological Mind. Word Books, ISBN 0876804636

- Evans, C. Stephen. (1996). "Introduction" in Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard, trans. by C. Stephen Evans and Sylvia Walsh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521848107

- Gardiner, Patrick. (1969). Nineteenth Century Philosophy. New York: The Free Press. ISBN 9780029112205

- Garff, Joakim. (2005). Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography, trans. by Bruce Kirmmse. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691091655

- Hall, Sharon K. (1983). Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Detroit: University of Michigan. ISBN 9780810302211

- Hannay, Alastair. (2003). Kierkegaard: A Biography (new ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521531810

- Hannay, Alastair and Gordon Marino (eds). (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477190

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. (1979). Phenomenology of Spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198245971

- Hong, Howard V, and Edna Hong. (2000). The Essential Kierkegaard. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691033099

- Howland, Jacob. (2006). Kierkegaard and Socrates: A Study in Philosophy and Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521862035

- Houe, Poul, and Gordon D. Marino, Eds. (2003). Søren Kierkegaard and the words. Essays on hermeneutics and communication, Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzel.

- Hubben, William. (1962). Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka: Four Prophets of Our Destiny. New York: Collier Books.

- Hutchens, Benjamin C. (2004). Levinas: a guide for the perplexed. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780826472823.

- Jaspers, Karl. (1935). Vernunft und Existenz. Fünf Vorlesungen. (German) Groningen.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (2001). A Literary Review. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0140448012

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1992). Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691020825

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1985). Johannes Climacus, De Omnibus Dubitandum Est, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691020365

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1976). Journals and Papers, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253182395

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1999). Provocations, edited by Charles Moore. Rifton, NY: Plough Publishing House. ISBN 9780874869811

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1989). The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691073546.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1998b). The Moment and Late Writings, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691140810

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1998a). The Point of View. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691058555.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. (1978). Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age, A Literary Review, trans. by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691140766

- Kosch, Michelle. (1996). Freedom and reason in Kant, Schelling, and Kierkegaard. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199289110

- Lippitt, John. (2003). Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415180474

- Lowrie, Walter. (1942). A Short Life of Kierkegaard. Prinecton: Princeton University Press.

- Lowrie, Walter. (1968). Kierkegaard's Attack Upon Christendom. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. (2001). "Once More on Kierkegaard" in Kierkegaard after MacIntyre. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 081269452X

- MacKey, Louis. (1971). Kierkegaard: A Kind of Poet. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812210425

- Malantschuk, Gregor, and Howard and Edna Hong. (2003). Kierkegaard's concept of existence. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press. ISBN 9780874626582

- Matustik, Martin Joseph and Merold Westphal (eds). (1995). Kierkegaard in Post/Modernity. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253209676

- McGrath, Alister E. (1993). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0631198962

- Mooney, Edward F. (2007). On Søren Kierkegaard: dialogue, polemics, lost intimacy, and time. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754658221

- Oden, Thomas C. (2004). The Humor of Kierkegaard: An Anthology. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069102085X

- Ostenfeld, Ib and Alastair McKinnon. (1972). Søren Kierkegaard's Psychology. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurer University Press, ISBN 0889200688

- Pattison, George. (2002). Kierkegaard's Upbuilding Discourses: Philosophy, theology, literature. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415283701.

- Pattison, George. (2005). The Philosophy of Kierkegaard. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773529878

- Popper, Sir Karl R. (2002). The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol 2: Hegel and Marx. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415290635

- Pyle, Andrew. (1999). Key philosophers in conversation: the Cogito interviews. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415180368

- Rorty, Richard. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521367816

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. (1969). Being and nothingness: an essay on phenomenological ontology. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415040297

- Skopetea, Sophia. (1995). Kierkegaard og graeciteten, En Kamp med ironi. Copenhagen: C. A. Reitzel. ISBN 8774219634 (In Danish with synopsis in English)

- Staubrand, Jens. (2009). Jens Staubrand: Søren Kierkegaard's Illness and Death, Copenhagen: Soren Kierkegaard Kulturproduktion. ISBN 9788792259929. The book is in English and Danish.

- Staubrand, Jens. (2009). Søren Kierkegaard: International Bibliography Music works & Plays, New edition, Copenhagen: Soren Kierkegaard Kulturproduktion. ISBN 9788792259912. The book is in English and Danish.

- Stern, Kenneth. (1990). "Kierkegaard on Theistic Proof" in Religious Studies. Cambridge, Vol. 26, p. 219-226.

- Stewart, Jon. (2009). Kierkegaard's International Reception, Vol. 8. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754664963

- Updike, John. (1997). "Foreword" in The Seducer's Diary by Søren Kierkegaard. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691017379

- Walsh, Sylvia. (2009). Kierkegaard: Thinking Christianly in an Existential Mode. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199208364

- Watkin, Julia. (2000). Kierkegaard. Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 9780826450869

- Westfall, Joseph. (2007). The Kierkegaardian Author: Authorship and Performance in Kierkegaard's Literary and Dramatic Criticism. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110193022

- Weston, Michael. (1994). Kierkegaard and Modern Continental Philosophy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415101204

- Westphal, Merold. (1996). Becoming a self: a reading of Kierkegaard's concluding unscientific postscript. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue Press. ISBN 9781557530899

- Westphal, Merold. (1997). "Kierkegaard and Hegel" in The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521477190

- Wyschogrod, Michael. (1954). Kierkegaard and Heidegger. The Ontology of Existence London: Routledge.

Web

- Creegan, Charles. "Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard". Routledge. http://home.clear.net.nz/pages/ccreegan/wk/chapter1.html. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- Desroches, Dominic. « The Exception as Reinforcement of the ethical Norm : the Figures of Abraham and Job in Kierkegaard's ethical Thought » in "Existentialist Thinkers and Ethics". Queen’s-Mc Gill University Press. http://mqup.mcgill.ca/book.php?bookid=2015. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- Hampson, Daphne. Christian Contradictions: The Structures of Lutheran and Catholic Thought. Cambridge, 2004

- Kangas, David. "Kierkegaard, the Apophatic Theologian. David Kangas, Yale University (pdf format)" (PDF). Enrahonar No. 29, Departament de Filosofia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. http://ddd.uab.cat/pub/enrahonar/0211402Xn29p119.pdf. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- Katz, Claire Elise. "The Voice of God and the Face of the Other". Penn State University. http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/journals/tr/archive/volume10/Katz.html. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- Kirmmse, Bruce. "Review of Habib Malik, Receiving Søren Kierkegaard". Stolaf. http://web.archive.org/web/20080520040010/http://www.stolaf.edu/collections/kierkegaard/newsletter/issue39/39002.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- Lippitt, John and Daniel Hutto. (1998). "Making Sense of Nonsense: Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein". University of Hertfordshire. http://www.sorenkierkegaard.nl/artikelen/Engels/033.%20MAKING%20SENSE%20OF%20NONSENSE.pdf. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- MacDonald, William. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Søren Kierkegaard.

- Masugata, Kinya. "Kierkegaard's Reception in Japan". Kinya Masugata. http://www.kierkegaard.jp/masugata/sk2eng.html. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- McGee, Kyle. "Fear and Trembling in the Penal Colony". Kafka Project. http://www.kafka.org/index.php?id=185,290,0,0,1,0. Retrieved 2010-03-01.